United in Progress

- …

United in Progress

- …

Nooky

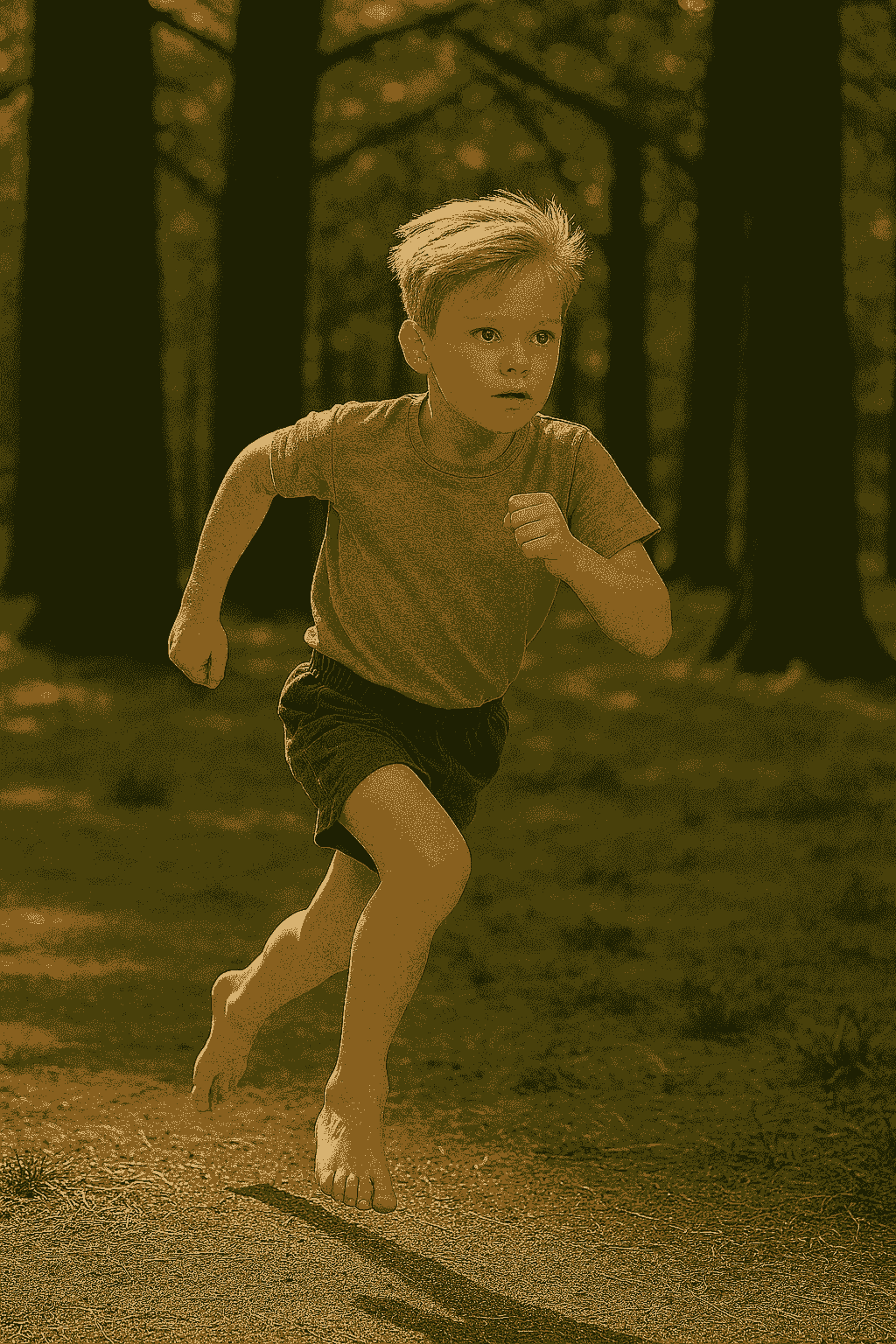

The Boy Who Ran with Trees

Born into the Thomas family, in a new country still finding its shape,

grandfather was a white boy raised among kauri giants and Māori playmates.

They called him “Nooky”—a nickname stitched into memory,

though the spelling may be lost to time.

He never met his father until the man lay dying from a stroke.

His whole life, he’d been told his father was dead.

He also had an older brother he didn’t meet until his 60s—long after the war,

long after the dairy—because his brother had lived in Australia.

That kind of delayed reunion says everything about the silences families carry.

Raised on a farm by his mother alongside four older sisters (two of them twins),

Nooky learned early that life didn’t wait.

At five in the morning, before school in Papatoetoe, he’d be up churning butter.

His mother was a quiet force—deeply drawn to the islands.

She once returned from Fiji with a heavy suitcase full of large seashells

and planted them in her garden like offerings.

Her home was open to islanders who needed a place to stay.

She never charged them, just welcomed them in.

Hospitality wasn’t a transaction—it was a rhythm.

Look after the people and they will look after you.

Hazel, one of his sisters, never had children but loved animals fiercely.She married Roy, who later served in WWII alongside Nooky.

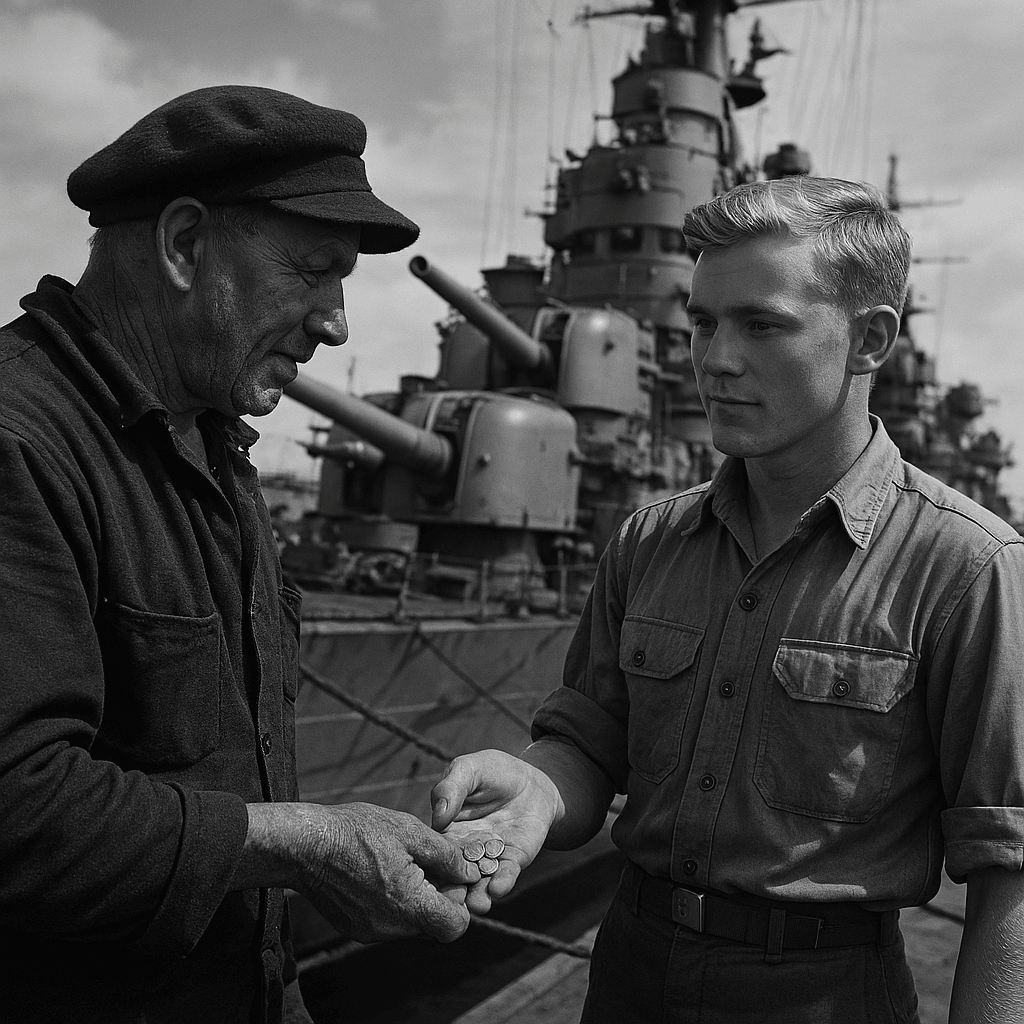

The war shaped him—he fought several battles and

trained in Egypt to go behind enemy lines,

his blond hair and blue eyes making him a candidate for covert work.

But a bombing buried him in sand.

He was dug out alive, but the sand damaged his eye

so badly it had to be removed so it could be cleaned.

From then on, one eye was darker than the other.

Still, he was ready to return to war when peace was declared.

He’d met a girl at a dance before shipping out and sent her postcards from the front

—updates on who he was with, how he cleaned behind his ears

(either a hygiene concern or a cheeky nod to her listening reminders).

After the war, they married.

He worked on the railways for a time and built a modest home at 22 Harding Ave, Panmure.

Later, he was inducted into the Waipuna Lodge as a Freemason.

He and his wife had one daughter.

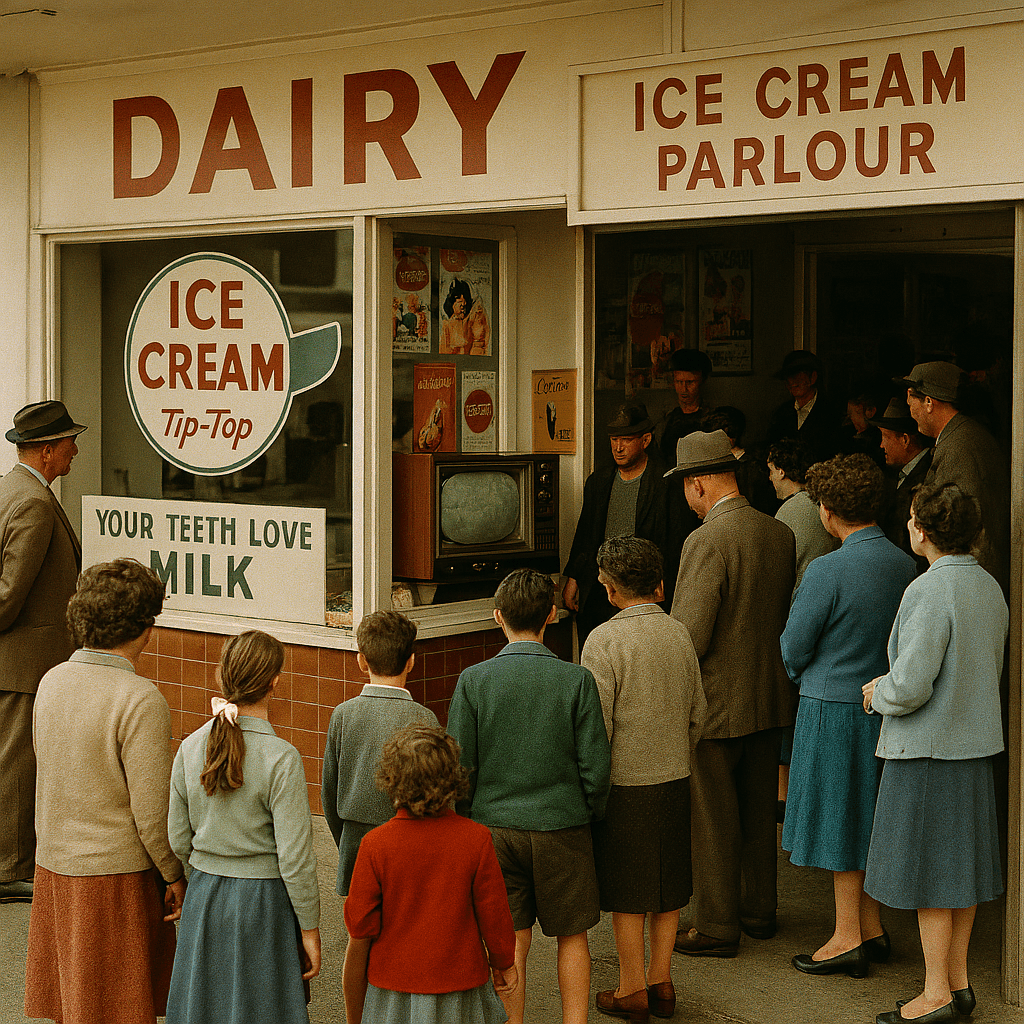

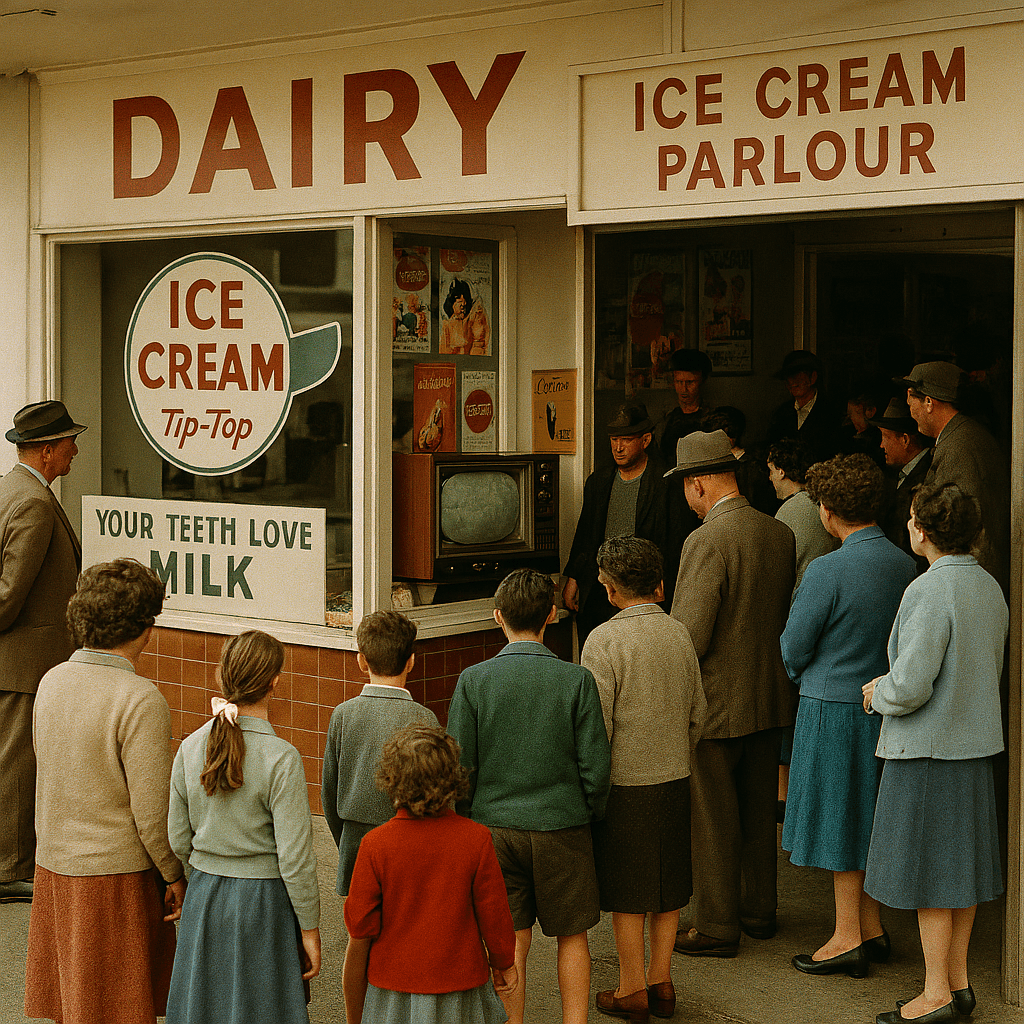

They ran a dairy in Howick, and Nooky had a knack for business.

If he saw a child alone, he’d offer them an ice cream—not just kindness, but strategy.

That child would bring their family and friends back.

My grandmother and mother weren’t thrilled about the cleanup,

but he understood how word-of-mouth worked.

In the 1960s, when TVs were rare in New Zealand, he bought one for the dairy—

the first in Howick. Locals gathered to watch.

Eventually, he sold the shop and became a real estate agent,

the first in the country to sell $1 million worth of property

when the average house was around just $6,000.

He once told a young couple to go away, save for two years, and come back.

They did set their goal—and bought their first home from him.

When his daughter married and had a baby,

he bought a section in Pakuranga so they could return from Australia and be close.

He was horrified by the volatile interest rates she faced—

so different from the fixed terms of his era.

When she separated from her husband, he helped her secure a loan to buy another home nearby.

His own house was full of fruit trees and a garden he plowed every year.

The family never went without food, but they never felt wealthy.

He wore shorts year-round and only put on trousers for special occasions.

Brown Roman sandals were his signature—worn until the end.

Christmas was sacred. He’d set up a long table in the living room,

bring out the piano accordion or mouth organ, and taste-test the wine (half a glass, of course)

before topping up everyone else’s.

Drinking was quiet —except on Christmas and ANZAC Day, when he was allowed.

They saved all year for it—a Christmas break at Waihi Beach,

where the surf club wasn’t just a landmark, it was family.

His wifes brother was deeply involved, and so were his children—

part of the crew that kept things running,

taught the next generation, and anchored the summer rhythm.

Every night during the holidays, they’d fundraise with quick-fire raffle tickets—

small stakes, big laughs, and a community stitched together by shared purpose.

The beach became a seasonal home base, where family dropped by, stayed late,

and caught up over shared meals and sunburnt stories.

Four grandchildren crammed into the car,

knees pressed to seats, no snacks allowed—

but if you were lucky, you might be handed a Mackintosh or a Mintie,

like a tiny reward for good behaviour.

Every trip within driving distance of Auckland became a memory—

tight-packed, laughter-filled, and threaded with the kind of joy

you only get when everyone’s in it together.

He loved cars and once owned a Jaguar, but after it was vandalized,

he switched to more modest vehicles.

In retirement, he hung out at the local garage, relocating cars for people.

His man cave downstairs had a pool table and a drink stash—

his way of giving the boys space and keeping my grandmother sane.

When I lived with them, he’d hand me a spiked drink after work and ask how my “Coke” was.

One time, when a video player broke and the shop refused to help,

he simply picked up another and walked out the door.

Fairness, in his eyes, wasn’t negotiable.

On a bus in Australia, Nooky found a small bag—

inside, a packet of money and a cheque book.

He didn’t hesitate. Took it to the bank, granddaughter by his side,

teaching her that it wasn’t a windfall, but someone’s hard-earned pay.

The money was returned to the band who’d left it behind after a gig.

No applause. Just the quiet act of doing what’s right.

They thanked him personally, gifting a book on Australia.

He’d been there many times. He didn’t need it. But he accepted it with quiet grace—

because sometimes, the gesture matters more than the gift.

Because that’s how it works.

You do a kind thing, and the universe pays it forward.

In his final days, he bought a new car for his wife—

one that would see her and their daughters through the years ahead.

He had fair skin and developed melanoma,

which eventually spread to his bowel and took his life.

He volunteered for experimental medicine, not just for himself,

but to help scientists improve outcomes for future generations.

But his legacy—hard work, fairness, cheek, and quiet rebellion—lives on.

He built systems that worked when official ones didn’t.

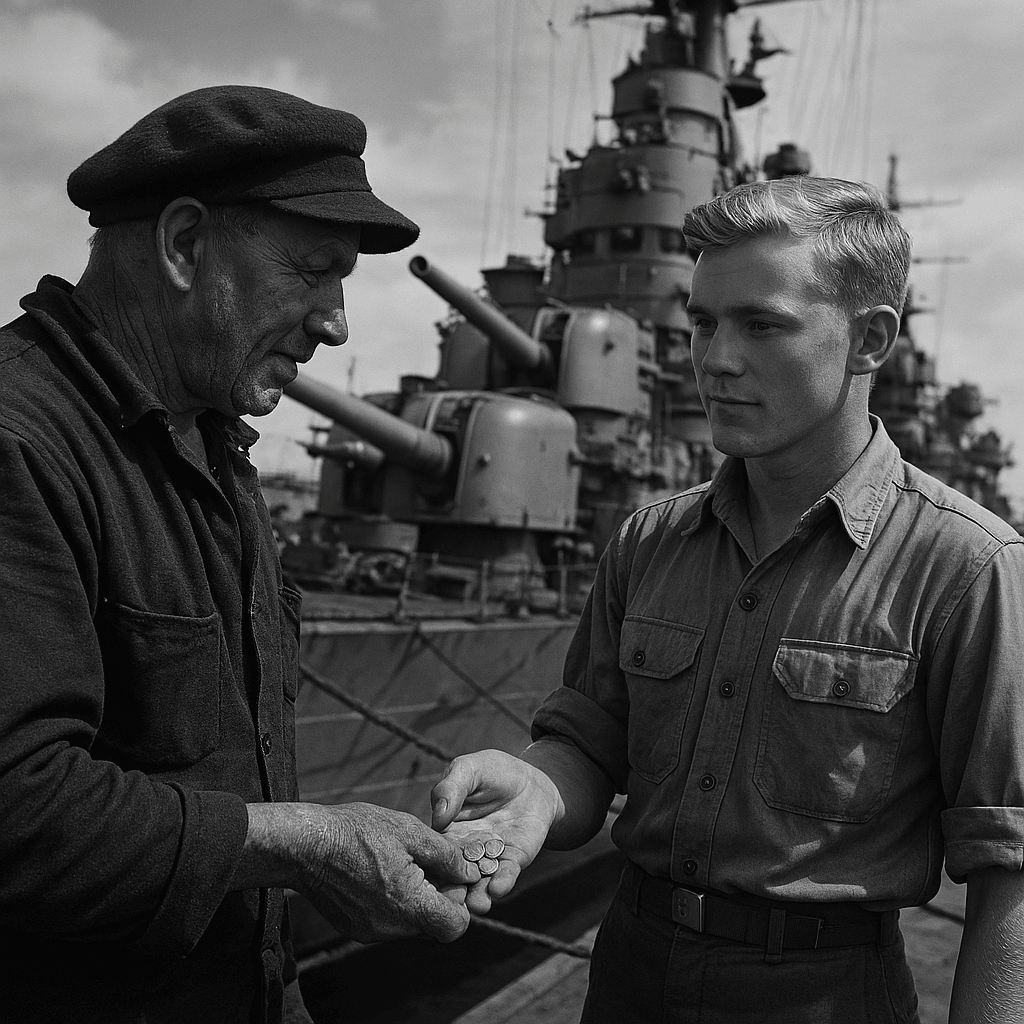

He shared a drink and returned $5 he borrowed

from a stranger on his way to war years later,

just because he’d promised when he had no money.

He wore sandals like armor and ran his life with clarity, joy,

and just enough mischief to keep things interesting.

He never thought he’d see that man again. But the gesture stuck—

etched into memory, carried through time.

And when they crossed paths years later,

the drink said everything words didn’t

Proudly built with Strikingly.