MOV ITx Deep Dive: Why Oliver’s Still Asking for More Cake

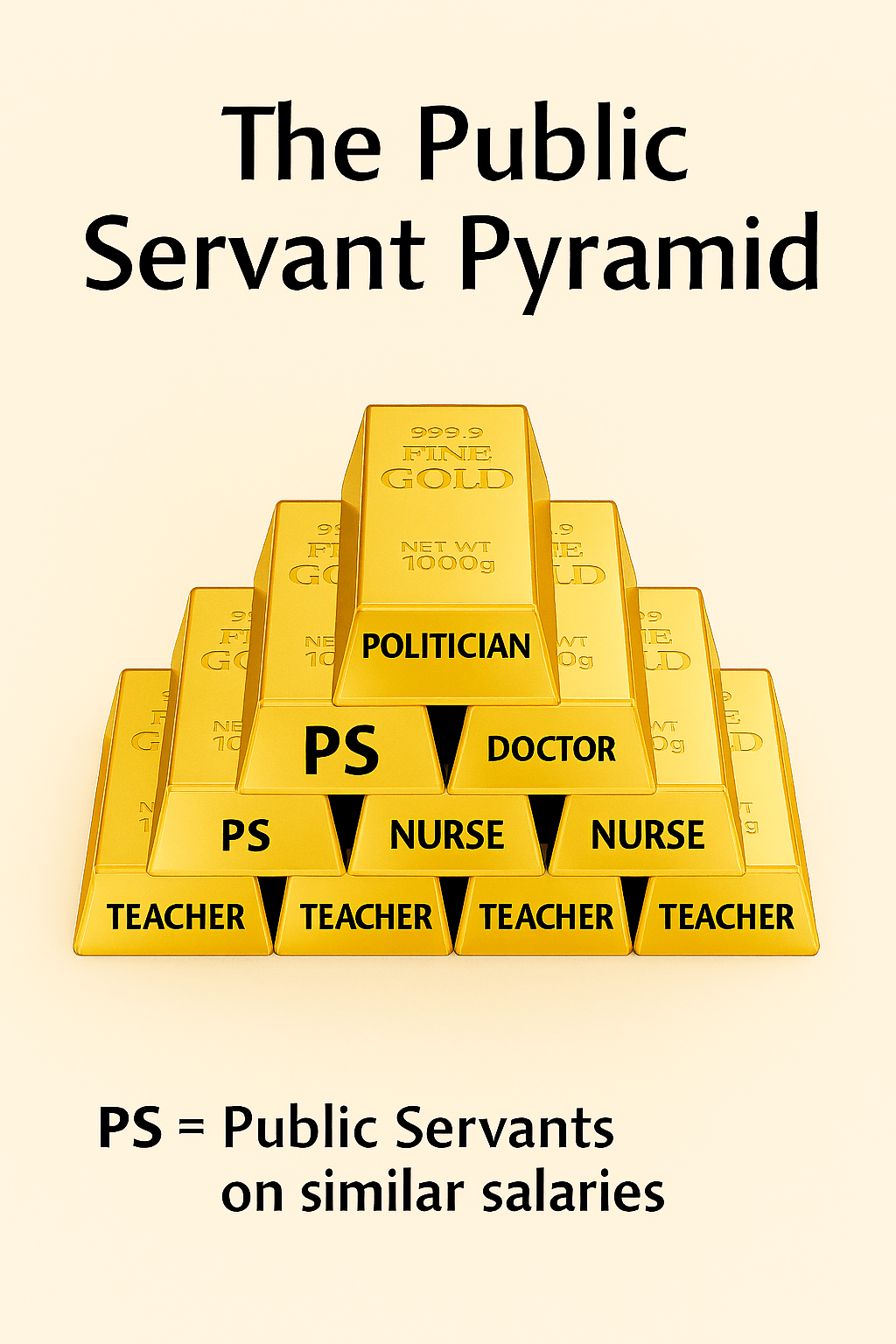

The system didn’t set out to create a class divide—but it did. Through compounding pay structures, percentage-based increases, and legacy inertia, it built a hierarchy where those on lower wages fall further behind with every budget cycle. Teachers, nurses, and carers—professions dominated by women—aren’t just underpaid, they’re structurally sidelined. Meanwhile, those at the top start with a bigger slice and get rewarded for having it. The facts don’t lie. If you’re brave enough to keep reading, we’ll show exactly how this happens—and why Oliver’s bowl is still empty.

Percentage-based pay rises sound fair—until you do the math. A 5% increase on a $200,000 salary adds $10,000. That same 5% on a $60,000 salary adds just $3,000. The gap doesn’t just persist—it compounds. Every year, those at the top get a bigger boost, while those on lower wages struggle to keep pace with rising costs, stagnant conditions, and shrinking margins. And because nursing, teaching, and caregiving are female-dominated industries, the compounding isn’t just economic—it’s gendered.

This isn’t just about numbers—it’s about values. When the system consistently undervalues the work of those who teach our children, care for our sick, and support our most vulnerable, it sends a message: some contributions matter more than others. And when those underpaid roles are disproportionately filled by women, the gap becomes more than economic—it becomes cultural. It’s not just a pay issue. It’s a legacy issue. And it’s time we stopped pretending the system is neutral when the outcomes are anything but.

HOW DID IT HAPPEN?

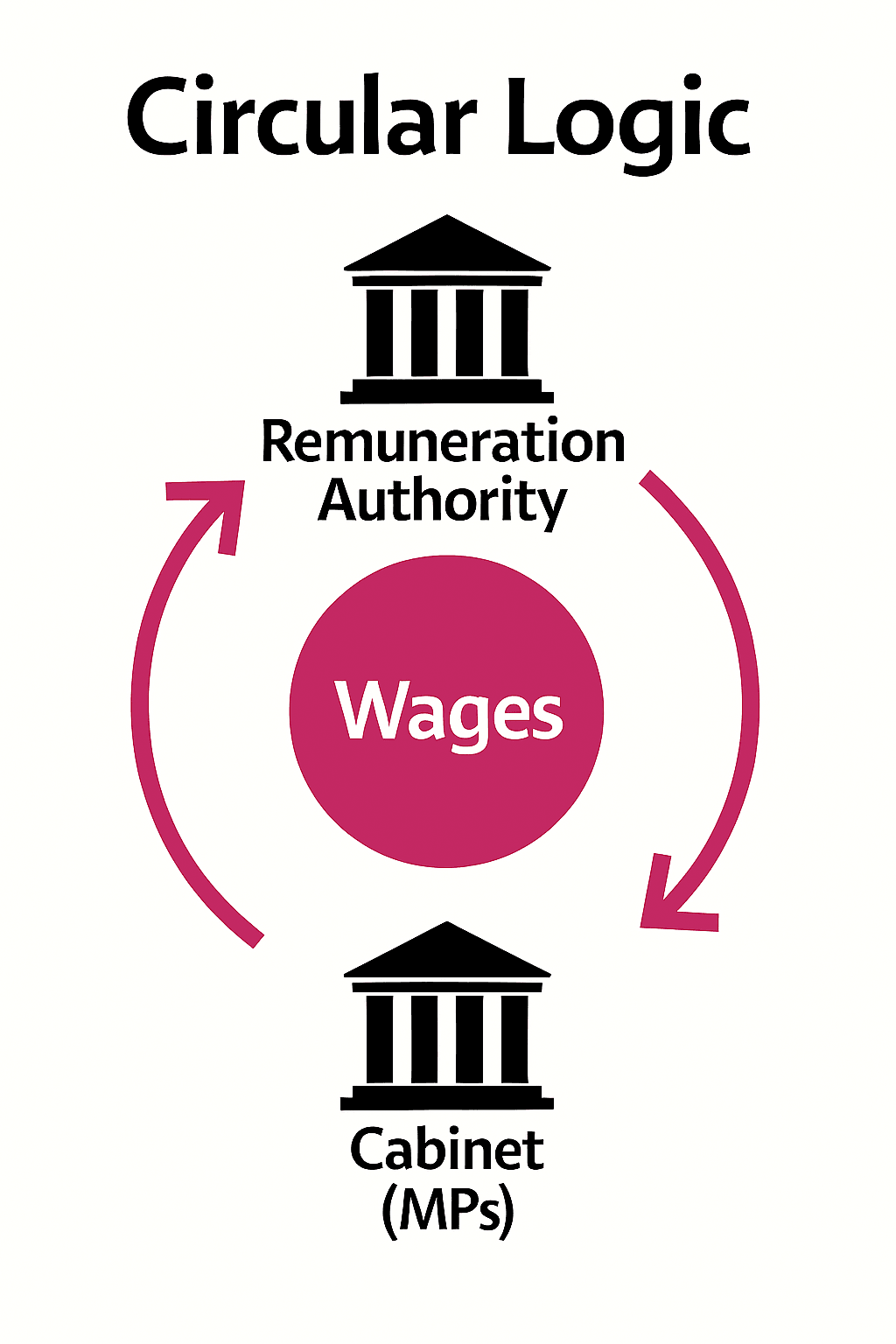

In New Zealand, wage logic isn’t linear for some—it’s circular.

Politicians don’t negotiate their own pay.

They outsource it to the Remuneration Authority, a regulator formally appointed by the Governor-General—on Cabinet’s recommendation.

That same Cabinet sets the Authority’s pay.

So while MP salaries rise through a closed loop of appointments and reviews,

public servants—teachers, nurses, doctors—must bargain, ballot, and strike.

Their wages aren’t valued equally.

They’re delayed, contested, and often eroded by inflation.

And when starting salaries stall and compounding losses mount,

the pyramid tilts—not just economically, but ethically.

Who sets? Who strikes? Who waits?

In this loop, the ones who wait are the ones who serve.

And the ones who serve are the ones who pay.

🏛️ Circular Reward System: You Scratch, I Rise

Politicians don’t negotiate their own pay.

They outsource it to the Remuneration Authority—

An “independent” body formally appointed by the Governor-General,

but only on the recommendation of Cabinet.

And here’s the kicker:

Cabinet also sets the Authority’s pay.

The Authority, in turn, sets the pay for all Members of Parliament.

So the loop isn’t just closed—it’s reward-coded.

• Cabinet recommends the Authority

• Governor-General appoints

• Authority sets MP pay

• Cabinet sets Authority pay

No ballots. No strikes. No inflation lag.

Just a tidy feedback loop with built-in incentives.

Meanwhile, public servants—nurses, teachers, doctors—

Must bargain with ministries run by those same MPs.

Raises are delayed, contested, and often below inflation.

And when they strike, they’re told to be patient.

But patience doesn’t compound. Privilege does.

The diagram says it all:

Two government buildings, two curved arrows, one red circle labeled “Wages.”

It’s not just circular. It’s self-reinforcing.

A civic feedback loop where the people who set the rules

don’t eat the same cake they serve.

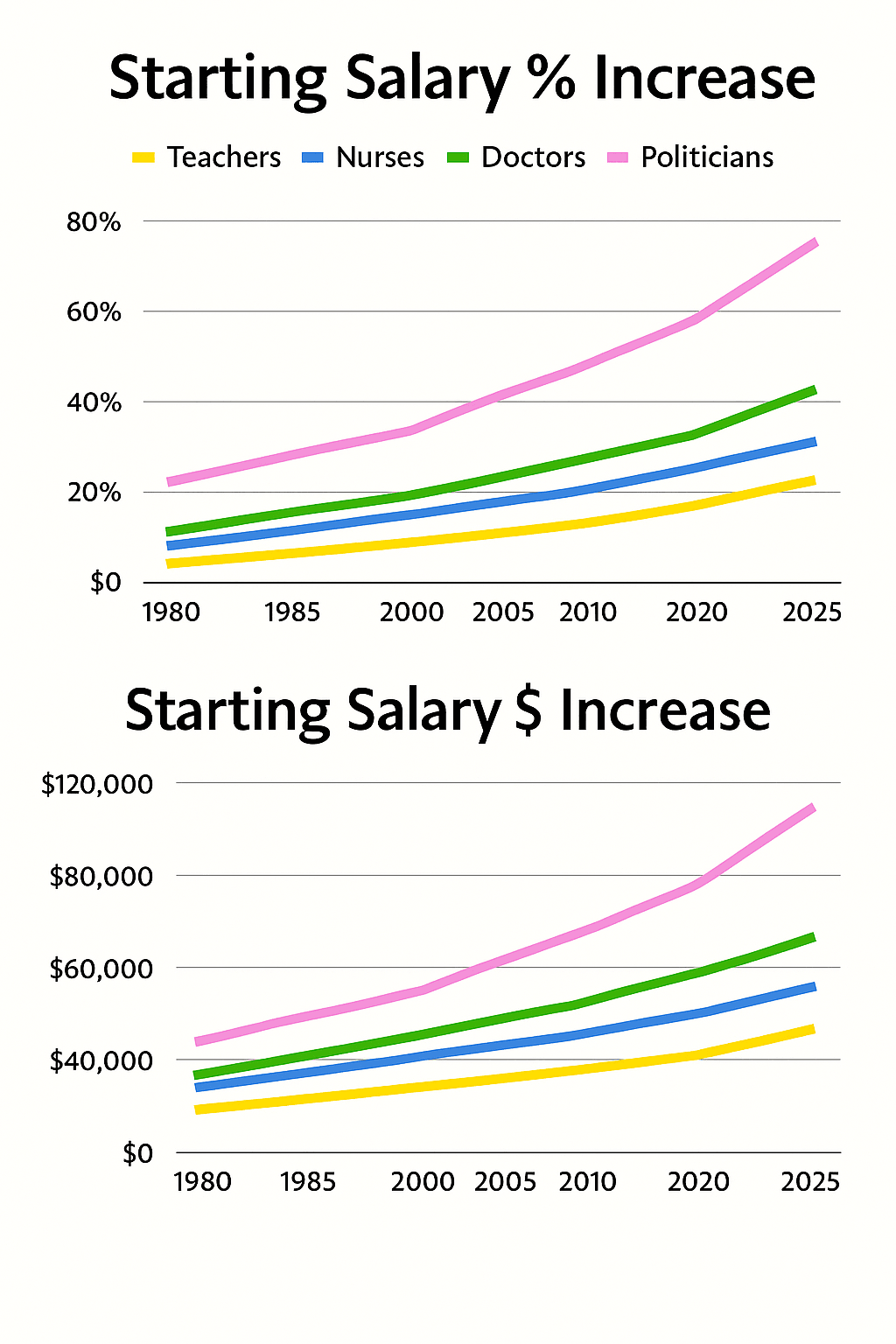

📊 Starting Wages: 1980–2025 and the Circular Reward Gap

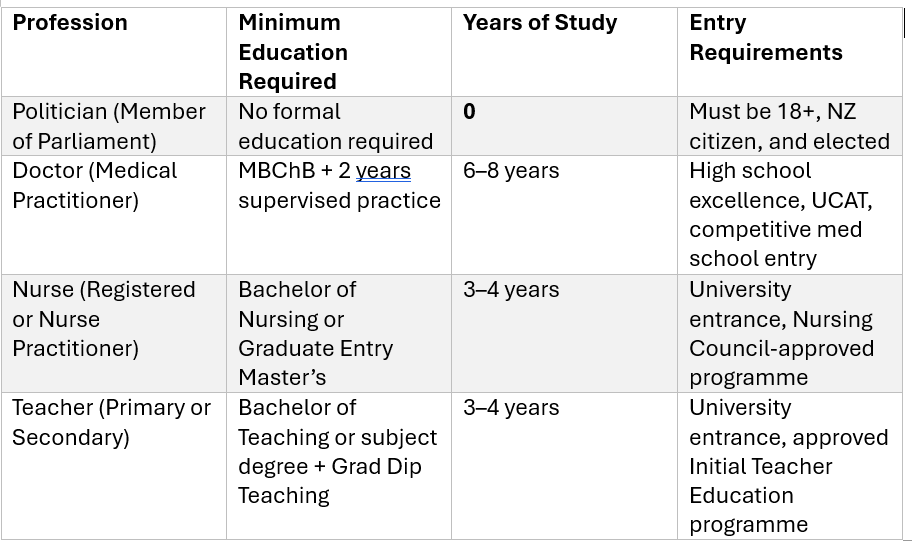

This graph tracks the starting salary increases for teachers, nurses, doctors, and politicians over 45 years. The disparities aren’t accidental—they’re structurally reinforced.

Since 1977, MP salaries have been set by the Remuneration Authority, a regulator formally appointed by the Governor-General on Cabinet’s recommendation. Cabinet also sets the Authority’s pay. That’s a closed feedback loop—a circular reward system where MPs benefit from automatic, benchmarked increases without needing qualifications, experience, or negotiation.

Meanwhile, teachers, nurses, and doctors must:

• Earn formal qualifications

• Complete years of training

• Enter underpaid, overworked systems

• Bargain, ballot, and strike for every raise

And yet, the graph shows that MPs have received the steepest increases in both percentage and dollar terms—despite requiring zero years of experience and no formal qualifications to enter Parliament.

This isn’t just a wage gap. It’s a civic distortion.

The people who legislate pay don’t live the protocols they impose.

And the ones who serve—who train, qualify, and show up—are the ones who wait.

📈 Why Comparing % and $ Matters: The Compounding Advantage

When politicians receive a 10% pay rise, it’s not the same as a nurse or teacher receiving 10%.

Because the starting point matters—and the math compounds.

This is compound logic:

Each raise builds on the last.

The higher your starting salary, the larger your slice of the pie becomes—automatically.

Let’s break it down with a non-factual, illustrative example:

• Suppose an MP earns $100,000 in 1995.

• A 10% raise lifts their salary to $110,000.

• In 2000, they receive another 10% raise—not on the original $100,000, but on the new $110,000.

• That brings their salary to $121,000.

That’s a $21,000 total increase, not just $10,000 twice.

If the raises were flat—$10,000 each time—the total would be $120,000.

But because each raise builds on the last, the extra $1,000 comes from compounding.

Now imagine this pattern repeating every few years.

The higher your starting salary, the larger your slice of the pie becomes automatically—even if the percentage stays the same.

Meanwhile, other public servants with lower starting wages get smaller dollar increases, even if the percentage looks similar.

And when their raises lag behind inflation, the compounding works against them.

So when graphs show percentage increases, they can mask privilege.

The real audit lives in the dollar growth—and who gets to start higher, rise faster, and skip the ballot.

📊 Why % Increases Can Mislead: The Compounding Gap in Starting Salaries

When comparing wage growth across professions, percentage increases often sound fair—until you map them in dollar terms and compound over time. Here's how it plays out:

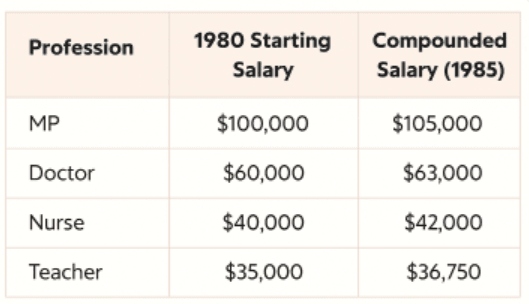

🔍 Example: 5% Increase from 1980 to 1985

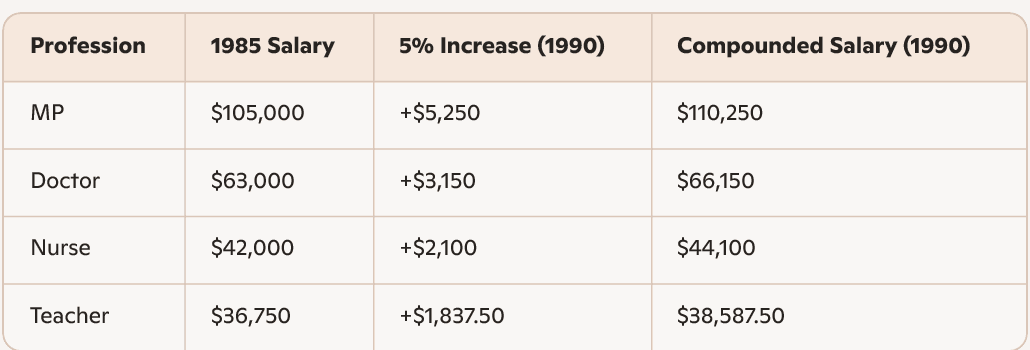

Now apply another 5% increase in 1990:

🧠 What This Shows:

• Same % increase, wildly different $ gains.

• MPs gain $10,250 over 10 years; Teachers gain $3,587.50.

• The gap compounds, not just grows linearly.

• Even a lower % increase on a high salary yields a larger absolute gain.

🧮 The Legitimacy Ledger: Who Sets, Who Signs Off?

The trend is clear: MP wages have risen steeply, far outpacing the starting salaries of teachers, nurses, and doctors.

This isn’t just a market outcome—it’s a regulatory design flaw.

MP pay is set by the Remuneration Authority, a body formally appointed by the Governor-General on Cabinet’s recommendation.

That same Cabinet sets the Authority’s pay.

So while public servants must negotiate, strike, and wait, MPs benefit from a closed-loop reward system—no ballots, no inflation lag, no qualification requirements.

And that raises a civic question:

Why are only MPs protected by this Authority?

Why is there no equivalent independent review for frontline public servants?

Why is there no higher sign-off—no cross-party, citizen-led, or constitutional check—on the wages of those who legislate but don’t serve in hospitals, classrooms, or clinics?

This isn’t just about pay.

It’s about legitimacy, transparency, and civic equity.

Because when the people who set the rules also benefit from the loop,

the system isn’t just circular—it’s self-serving.

Reward Oversight

This isn’t a one-off.

The steep rise in MP wages has unfolded across successive governments, regardless of party.

It’s not partisan—it’s structural.

And the disparity between MP pay and public servant starting wages isn’t just growing—

It’s entrenching a classed system, where those who legislate are rewarded by a loop they control,

while those who serve—teachers, nurses, doctors—are left to bargain, ballot, and wait.

This is what happens when self-regulation masquerades as independence.

The Remuneration Authority may be formally appointed by the Governor-General,

but it’s Cabinet-recommended and Cabinet-paid.

That’s not oversight. That’s circular privilege.

And when the same loop repeats across decades,

it doesn’t just distort pay—it distorts legitimacy.

Because the people who benefit from the system

aren’t the ones holding it accountable.

The numbers aren’t neutral. The system isn’t accidental. And the gap isn’t closing. But clarity is a form of resistance—and documentation is a form of repair. When we trace the compounding, gendered, and structural patterns baked into pay systems, we don’t just expose the cracks—we start mapping the fix.

These are the voyages of Random Circuits, boldly entering the arena of ideas that disrupt, challenge, and transform.