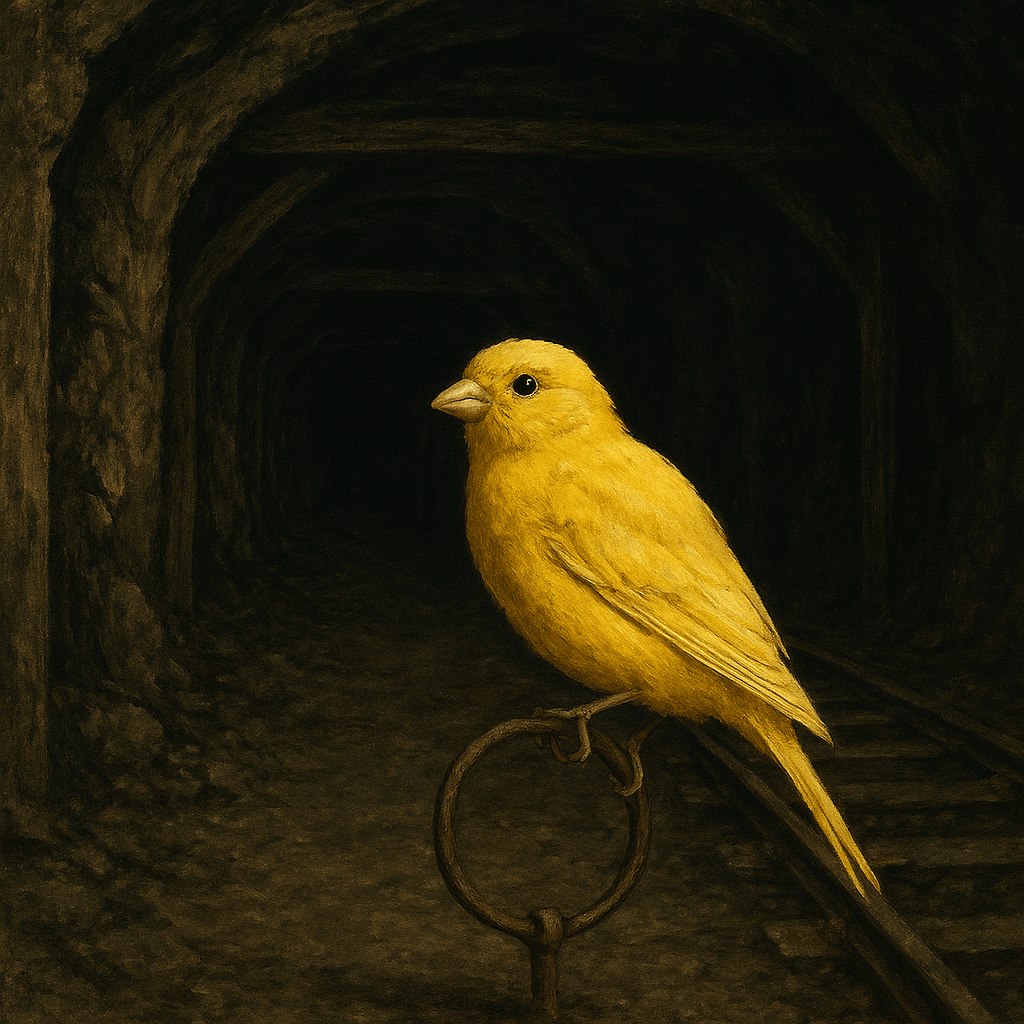

When the canary stops tweeting, it’s already too late. Preventable harm isn’t inevitable. Workplace disasters are never as sudden as they seem. Long before the explosion, the collapse, or the fatal shift, there are warning signs — the modern equivalent of a canary falling silent. Yet across industries, these signals are ignored, normalised, or buried under production pressure. This piece looks at the pattern behind preventable harm and asks a simple question: if we can rate food safety on a door, why can’t we rate workplace safety the same way?

Every time a major disaster occurs, the public hears the same phrases:

“Unforeseeable.”

“Tragic.”

“A one‑off failure.”

Yet across Pike River, BP Deepwater Horizon, Boeing 737 MAX, Grenfell, forestry deaths, construction falls, farm fatalities, and countless industrial incidents, a consistent pattern emerges. These events do not erupt from nowhere. They arise from the same behaviours, repeated across industries, countries, and decades.

The danger is rarely the explosion, the collapse, or the fire itself.

The danger is the behaviour that leads to it.

And that behaviour is almost always the same:

Institutionalised risk‑taking.

Danger by Design

Companies do not deliberately set out to harm people.

But they routinely make decisions that create the conditions for harm.

They ignore maintenance.

They rush production.

They silence workers.

They normalise shortcuts.

They treat near‑misses as proof that “the system works.”

They reduce risk to a spreadsheet number — until the day it becomes a headline.

This is danger by design.

Not because anyone wants a disaster, but because the incentives reward pushing limits and punish slowing down.

At Pike River, methane alarms were normalised. Ventilation was inadequate. Workers raised concerns. Inspectors visited. The warning signs were visible. But the regulator lacked the authority to shut the mine down — and the company lacked the will to stop production.

The behaviour was evident long before the explosion.

The system simply wasn’t designed to intervene.

The People Who Live With the Danger See It First

Those closest to the risk understand it best.

Workers see the leaking valve, the faulty sensor, the overloaded shift, the machine overdue for servicing. They feel the pressure to “push through.” They recognise when conditions are unsafe.

Those making the decisions are too far from the danger to feel it.

They see cost centres, productivity targets, and maintenance budgets.

They see risk as a number — until the day that number becomes a casualty count.

When the safest person in a dangerous workplace is the one who stays silent, the system is broken.

Not Every Tragedy Is the Same

Some events belong to what can be called the great unknown — sudden natural hazards, geological failures, or unpredictable environmental shifts. These are the moments where inquiry is genuinely about learning, not blame.

A landslide triggered by unstable ground or extreme weather is not the same as:

• overdue maintenance

• ignored alarms

• unsafe equipment

• production pressure

• silenced workers

The great unknown is rare, unpredictable, and indifferent to human behaviour.

But the pattern emerging across high‑risk industries is different.

It is not the great unknown — it is the greatly ignored.

It is preventable harm caused by:

• shortcuts

• pressure

• normalised risk

• ignored warning signs

• decisions made far from the danger

If Food Safety Gets Public Ratings, Why Not Workplace Safety?

Food hygiene ratings are displayed on doors because the risk is invisible to customers. Yet food safety failures, while serious, rarely cost someone a limb or a life. Workplace danger is far more immediate — heavy machinery, heights, confined spaces — and the consequences are often catastrophic. Despite this, a café with a dirty kitchen must display a grade, while a worksite with repeated near‑misses or even a fatality displays nothing at all. One system warns the public. The other leaves workers in the dark.

Inquiry Is Learning — But Prevention Is Better

Every inquiry teaches something.

Every Royal Commission, coroner’s report, and WorkSafe investigation lays out the same sequence of ignored warnings, shortcuts, pressure, and normalised risk.

But these lessons arrive too late.

Inquiry is learning.

Prevention is better.

The pattern is clear:

the higher the production targets, the worse the working conditions become.

Profit grows when safety shrinks — and the people who benefit from the profits are never the ones standing next to the machinery, underground in the mine, or up on the scaffolding.

A Safety Rating System That Makes the Invisible Visible

Preventing disasters requires transparency, not trust.

A public safety rating system would expose the behaviour that leads to harm long before the harm occurs.

A Rating — Safe and Stable

Strong safety culture, reliable maintenance, workers able to speak without fear.

B Rating — Formal Warning

Early signs of shortcuts.

Minor issues forming a pattern.

A clear message: Fix these issues now, or the next inspection results in a C.

This removes the “we didn’t know” defence that appears after every preventable tragedy.

C Rating — Mandatory 2‑Week Shutdown

A C rating signals that the system has already failed.

It is triggered by:

• repeated issues

• ignored warnings

• unsafe patterns

• maintenance failures

• worker reports of danger

• early signs of a dangerous culture

• any severe injury or death on site (excluding natural causes)

A serious injury or death is not an unfortunate event.

It is the final symptom of a long chain of unsafe behaviour.

A mandatory 2‑week shutdown forces:

• repairs

• retraining

• cultural reset

• independent verification

This is not punishment — it is prevention.

D Rating — Mandatory 1‑Month Shutdown

A D rating reflects systemic failure.

It includes:

• high‑risk behaviour

• ignored alarms

• serious breaches

• normalised near‑misses

• workers afraid to speak

• a culture that prioritises production over safety

A 1‑month shutdown is the only responsible response.

E Rating — Emergency Shutdown (Effective Immediately)

An E rating is reserved for situations where the danger is so extreme or so unstable that operations cannot safely continue for another minute. It is the regulatory equivalent of pulling the emergency brake. While this level of intervention should be rare, the Pike River mine disaster showed that some risks escalate beyond warnings, shutdown periods, or corrective plans. In these cases, the only responsible action is an immediate evacuation and full halt to operations until independent experts (at least 2) confirm the site is safe. Once stabilised, the workplace may reopen under a D rating, reflecting that although the immediate threat has passed, the underlying system remains unsafe and requires major corrective action.

Two D Ratings → Full Suspension Until Fixed

At this point, the question is no longer how to help the business continue.

It is whether the business should continue at all.

Reopening requires:

• independent auditor sign‑off

• worker confirmation that conditions have changed

• demonstrable cultural improvement

QR Codes + Anonymous Reporting: The Modern Canary

Every workplace would display its rating at the entrance, with a QR code linking to the full audit report. The same QR code would also provide an anonymous reporting channel — a direct line for workers to report unsafe conditions without fear of retaliation.

Auditors see what is visible.

Workers report what is hidden.

Ratings reflect both.

This is the modern canary in the mine.

Not a bird that dies when conditions become unsafe —

but a system that listens to those who live with the danger every day.

Visibility Turns Safety Into Truth

For a safety rating to become a genuine organisational priority, it has to be visible. Displayed on the door, on the website, on the payslip — anywhere workers, customers, and shareholders can see it without digging. Visibility lifts safety out of internal paperwork and places it squarely in the realm of public accountability. When the rating is out in the open, it becomes part of the spreadsheet, part of the conversation, and part of the truth a business must stand behind.

Why This Matters

Society should not wait for the explosion, the collapse, the fire, or the death before acting.

The behaviour that creates disasters is visible long before the disaster itself.

Transparency changes behaviour in a way that internal audits and scheduled inspections never will.

At some point, the moral truth becomes unavoidable:

If a company cannot afford to keep people safe, then it cannot afford to be in business.

Bought to you by MOV ITx — we move it, prove it, then multiply it.

These are the voyages of Random Circuits, boldly entering the arena of ideas that disrupt, challenge, and transform.