The second time I went sailing, Dad decided it was time to teach us properly. The first attempt had been all bobbing around on flat water—boring, honestly. But sailing wasn’t just weekend recreation for him. My father had deep roots in it—competitive circles, Olympic-bound friends, and his own father a boat builder and the first commodore of the local sailing club. It was in the family DNA.

That day, he wanted us to experience the real thing. No drifting in still air. So we went out in the P-class on a windier day. He showed us how to counterbalance the boat by hanging over the side, how to tack, and what the start of a race looked like—even though we never actually raced.

I was keen to try it myself. The moment came: I leaned out, tried to shift my weight like I’d seen him do. But I wasn’t heavy enough. The boat tipped the wrong way, and I ended up half in the water, feet stuck in the straps. No life jacket—there simply wasn’t one—and the water was choppy, curling up over my face.

Still, I didn’t panic. Years of swimming and water safety had given me the kind of calm that kicks in when adrenaline wants to take over. I timed my breathing, held my position, and waited for Dad to wade in and tip the boat upright. He was laughing, called out, “You were going so fast! Want to go again?” My legs were bruised, I’d nearly drowned, and I was not interested in a repeat.

When emergencies hit, the first objective is always personal safety—stay visible, stay afloat, stay calm. Emergency responders train for that first phase: containment and stabilization.

I’d been swimming since I was little—not competitively, but enough to know how to stay afloat. That instinct gave me time. But skill alone isn’t safety. I probably should’ve had a life jacket. They weren’t exactly easy to move in back then—more marshmallow than mobility—but I’d wear one now, especially if I couldn’t swim.

We see it time and again. Not enough lifeboats on the Titanic. Boats going down with life jackets tucked in cabins no one can reach in a panic. Sure, it’s not practical to wear them all the time—but when the winds turn, is it worth your life to leave them stowed?

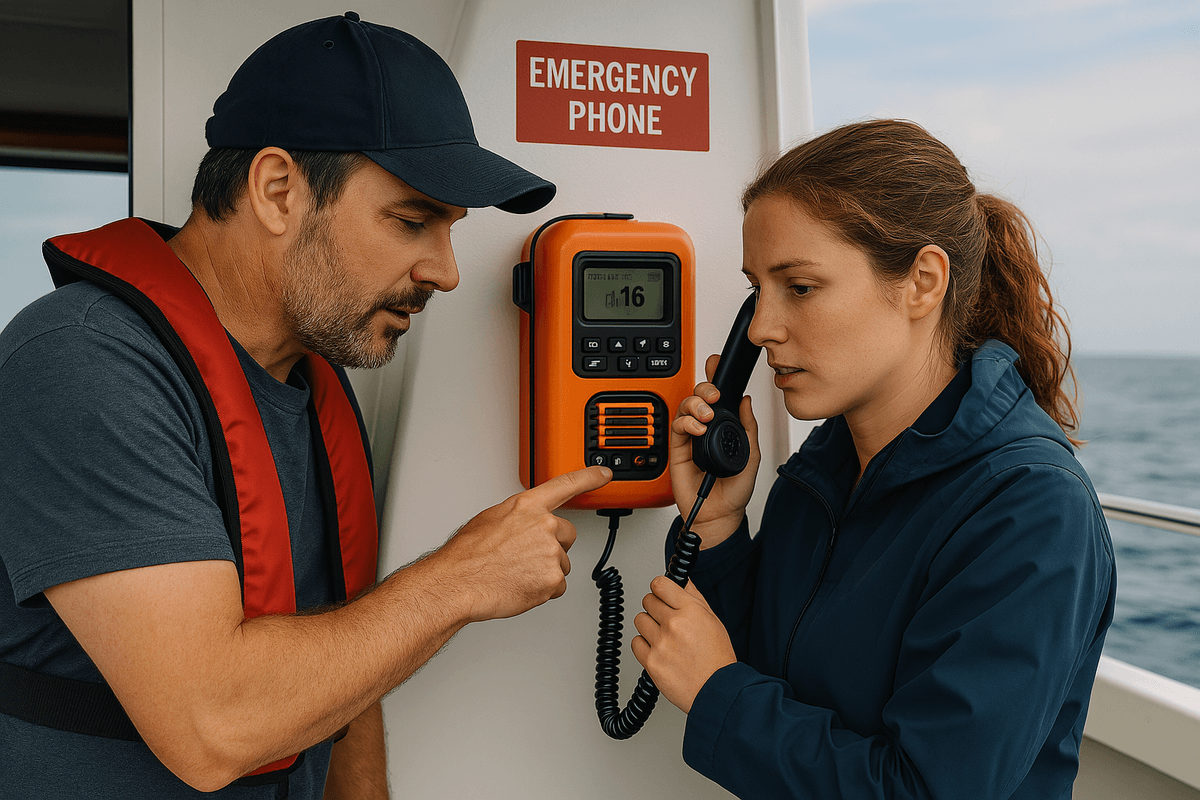

And it’s not just gear—it’s readiness. My brother once took me out on his boat, and what stuck wasn’t the scenery—it was the prep. Here’s the emergency phone. Here’s how to use it. Because the right equipment is one thing. Knowing how to use it under pressure? That’s what turns it into real protection.

We romanticize resilience—but real protection doesn’t rely on solo heroics. It’s built on coordinated care. You’re trained to hold steady long enough for the right mix of skills to step in: to assess the situation, decide how to stabilize, and begin recovery—not just of the person, but of the system they were navigating.

In unity, we safeguard not just ourselves, but the integrity of our response.

Emergency training teaches you how to react—not always to fix everything, but to stabilize until the team with the right mix of skills can step up. You learn to tread water, improvise, stay calm. But the real measure of protection isn’t just knowing what to do—it’s knowing you won’t be left to do it alone.

Sometimes experience is what keeps your head above water—and sometimes it’s knowing help’s on the way that lets you breathe a little easier.

You’re the star of your own story even when the storm tries to weather you .